Though it may seem obvious to point out, the camera is one of the most important parts of telling a visual story. There are so many nuances involved with cinematography it’s difficult to know where to start when explaining it’s significance. As Gus Van Sant said, “…I can’t think how anyone can become a director without learning the craft of cinematography.” Even if you’re not trying to create high art, it’s vital to know a few things about cinematography. Luckily for us, Joseph V. Mascelli wrote the Five C’s of Cinematography back in ’65 and his advice is still as relevant as ever. Mascelli compiled a list of the five most important aspects of cinematography that will contribute to the strength of your video project. Let’s unpack them here, shall we?

The Five C’s of Cinematography

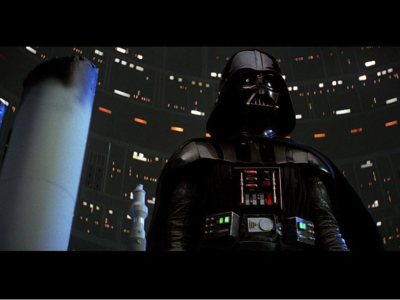

1. Camera Angles- This refers to the position of the camera while filming. While that may initially seem straightforward, there are numerous ways that the camera angle can influence the narrative significance of a scene. For example, a low-angle shot means that the camera is essentially looking up at the subject, which in turn makes the subject appear bigger and more dominant.

Darth Vader is consistently shot from a low angle, making him all the more ominous and threatening. Conversely, a high-angle shot is taken from above the subject, making them appear smaller as exemplified in this next clip from Psycho:

That scene is a masterpiece of cinematography from one of the masters of the art, Alfred Hitchcock. The high-angle camera in addition to the vulnerability of the location terrified audiences in 1960.

2. Continuity- Continuity refers to shooting things in a manner so that the scenes all interconnect and flow well, presenting a fluid sequence of events. Though mise-en-scène and editing contribute to the success of continuity, the camera is of equal or greater significance. Let’s take a look at one of the most amazing scenes in film history (Goodfellas) that demonstrates (along with an absolutely brilliant director) the camera’s role in continuity:

This is a wonderful example of a tracking shot or more specifically a Steadicam shot. The camera rolls for over two minutes without cutting once, all while demonstrating the nuances of storytelling at which the camera is so exceptional. We get a true insider’s glimpse of the world, mirroring the way Lorraine Bracco’s character must feel upon her introduction to Mafia life. The result is a truly immersive piece of filmmaking and a testament to the narrative power of continuity. More recently, Paul Thomas Anderson (Boogie Nights), Alejandro González Iñárritu (Birdman), and Alfonso Cuarón (Children of Men) have used similar techniques to great effect in the films I listed here. Birdman, in particular, takes continuity to a whole new level, by being carefully shot and edited to suggest that the film itself is essentially one long take.

3. Cutting- Cutting is putting together scenes in such a way that they become more than the sum of their parts. Continuity is important to keep in mind while shooting so that shots flow well into each other. Action at either the beginning or the end (or both) of each shot ensures that editors have a wealth of material to work with and produce the best possible cut. Here is an exhilarating example of continuity from The French Connection:

Conversely, you can use cutting to disorient the viewer, fracturing their perception of time within the film to make for a more challenging viewing experience. Jump cuts, so very favored by the French New Wave, is no better or worse than continuity editing, it just dramatically changes the flow. Here’s a clip from the film Oldboy that makes excellent use of jump cutting:

Through this non-linear presentation we as viewers get a sense of the ennui and boredom that the character Oh Dae Su is experiencing as he sits in jail. Regardless of implementation, cutting is paramount in presenting an engaging narrative.

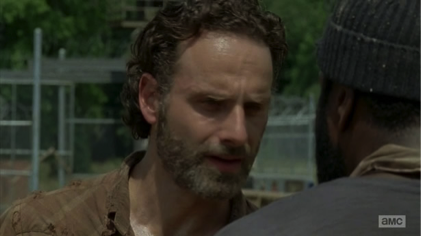

4. Close-ups- Close-ups typically consist of the subjects face and draw the viewer’s attention to what the character is feeling in that moment. It is a useful device for showing the viewer rather than telling them. Joan of Arc (the classic 1928 film, not the Mila Jovavich snooze-fest) is shot almost entirely in close-ups. Granted, this decision was likely born out of the limitations of cinema at the time it was made, but it’s still an effective example of the narrative weight that’s possible when using close-ups to portray emotion and motivation:

Poor Joan, having to deal with those mole-y clergymen. And who could forget this famous close-up that now mostly adorns white plaster walls in college dorm rooms across the country:

Just look at the madness on that face. There’s no mistaking his state of mind. Close-ups are invaluable in orienting your audience to character pathos and emotions.

5. Composition- Composition refers to the arrangement of actors and props in relation to the camera’s view of it. There are two shots, three shots, four shots, etc. referring to the number of character’s onscreen in a scene.

There are “dirty” shots, which generally refer to over-the-shoulder shots in which part of the subject is obfuscated by another character’s body in the foreground.

There are wide shots, mid shots, reverse and cutaway shots, static shots, etc. Far too many to list and they are probably due a dedicated post. So let’s get to the meat of composition and watch a masterful scene that is both beautifully filmed and demonstrative of the narrative importance of continuity:

I know, I know, everyone is tired of talking about Citizen Kane, but at least I’m not bringing up D.W. Griffith. “Deep focus,” you say… “I already know where you’re headed.” Well, you’re right. Developed by Gregg Toland on Citizen Kane, deep focus allowed for both the foreground and the background of a shot to be in focus. This in turn led to some significant developments in using the camera as an active storytelling tool. In this scene, we have poor young Charles Foster Kane in the middle, literally and figuratively, of an argument between the people determining his future. He’s framed within the window, which is thematically significant as the film is a window into Kane’s life. The deep focus and composition make this struggle visually apparent, enhancing the themes and storytelling.

So there they are: the Five C’s of Cinematography. The reason this list is so renowned is that each “C” is important to filmmaking but, when taken as a whole, they are invaluable in describing the camera’s role in telling great stories. The camera is to film as the brush and canvas is to art. Without the camera we wouldn’t have the cinema, and then we would all be forced to read or talk to each other or something. Surely I can’t be the only one to find some comfort in that.